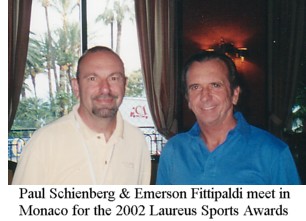

With Paul Schienberg, Ph.D.

Emerson Fittipaldi competed in 144 Grand Prix events and won 14 of them. He was the winner at the US Grand Prix in 1970; the Spanish, Belgium, British, Austrian, and Italian Grand Prix in 1972; the Argentinean, Brazilian and Spanish Grand Prix in 1973; the Brazilian, Belgian and Canadian Grand Prix in 1974; and the Argentinean and British Grand Prix in 1975. In addition, he won the Drivers Championships in 1972 and 1974.

Psyched: When I met you in New York City you said, “I have so many stories to tell you.” If you could tell me a story that would include the mental approach to driving a motor car, which seems to me the most intense focus you have to have,

Fittipaldi: A racing driver has to be a good driver. The first thing a driver must have is excellent anticipation. Must know what is going to happen before it is going to happen.

P: Can you do any of this before a race?

F: I am referring to when you are driving the racing car. You are going in one second the length of a football field. That means you brain is receiving information from your body what the car is doing physically, bumping, balance, performance. That information goes to the brain and you have to react by impulsive reaction. The car is an extension of the body. You have to feel what the car is feeling. You can not wait. You have to visualize a second or two ahead of your car what line you are taking, what you are going to do, before you get there because it comes too fast. Then you have to be thinking about strategy. When is going to be the next pit stop. How far am I to the end of the race? How well the car is balanced. Can anything be done to make it better? Then you have people behind, on the side and in front of you. You must consider all of these things at the same time.

P: And there are other great drivers around you?

F: I know if someone is coming from my right side. I could feel it. The driver Senna is one of the great racers. Gary Smith, when I came to America, taught me a great deal about racing. On a qualifying lap, a one-mile oval, short oval; one minute eighteen seconds. Very fast. Very quick time. After each practice, he taught me to go back to the motor room by myself, close my eyes and visualize the whole lap. I would have a stop watch and imagine how fast I had to go at different points of the track to qualify. I would project the ideal line at each point. I would already have seen what I should do at the start of the race. My first moves. The first corners. The first lap. I had already visualized it before I did it for real. I visualized the pit stops and how I would get out. How it would look. How long it would take. I would visualize the car fully balanced – how it should be during the race. How I would like my car to be behaving.

P: Did it ever change during with Indy racing?

F: Yes. Indy car racing is much more aggressive. I was extremely aggressive from the start. Smith taught me how to visualize the race. It made me calmer before the race. I was able to sleep before the race. I wanted to be the best in the world. You had to decompress the pressure before the race. I taught my heart to relax. I lay down before the race. It gave me more energy just before the race. Half-hour before the race you have the butterfly feelings. Another way to relax was to make all the connections to my uniform and open my visor. I was in my office. I relaxed in the driver’s seat. Also, I am very religious. It gave me peace of mind all my career.

P: Each race has an unknown risk.

F: In fact, all of life is a risk. You can be hit by a car crossing the street. The World Trade Center. I lost friends inside and outside of racing. I was extremely lucky. I had some huge crashes and yet I am still here, thanks to God. When I began to drive Formula I in the 1970’s, the odds of surviving was 7 to 1. Incredible high risks. The odds of surviving now are like 800 to one. It is safer to race now because of the changes made to the vehicles (cockpit), track and equipment that is worn and inside the car. During my crash in Michigan, it happened at 12g’s. If it had happened five years sooner, I would have been dead. Now during a crash the driver may feel 100g’s and walk away.

P: How did you get interested in motor car racing?

F: My father was a motor race journalist in Brazil. When I was five years old, he took me to a motor race and I loved it. That is what I want to do in life.

P: Did you ever get behind the wheel and feel that it was not your day?

F: Yes. I was at the Austrian Grand Prix in 1976. It was rainy, thunder storm. There was a lot of water on the track. Zero visibility. I have to accept risk as a racing driver. But, this is beyond what I should expect. I should not be here. I was not scared but I was for the first time in that race I decided I should not be in this sport and I should retire.

P: What did you feel about Schumacher and his slowing up?

F: It bothered me a great deal. It took away the spirit that the sport used to have. It doesn’t matter how professional you are – it is still sports. You are there to win because that is the name of the game. The racing driver’s mind has to have the ability to have amazing anticipation, coordination, and reflex. Because of the speed the car goes. When you come to a cross road with no traffic light, if I can see what the driver is going to do before he does it, it requires great anticipation.

P: Was there a driver that gave you the most trouble in competition?

F: At the beginning, it was Jackie Stewart. One year he won the world championship. The next year, I won it. Third year he won. And the fourth year I won. I learned a lot from him. Then I learned a lot from Nicki Lauda. And then there was Andretti. When I came to America Al Unser, Jr. was very difficult. And Bobby Unser. I never won at Monaco and Long Beach. I missed so much not winning here at Monaco. Always had mechanical problems at Monaco. I was driving Lotus. I have much sadness about Monaco. . .